Originally posted on IdahoEdNews.org on August 10, 2023

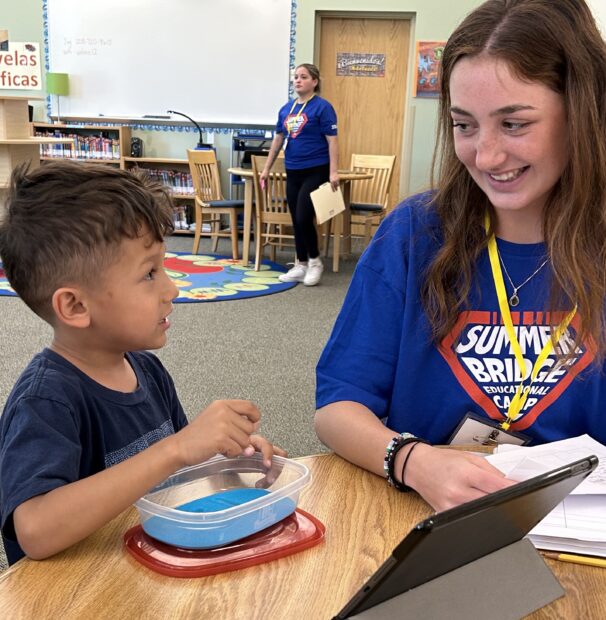

Effective reading curriculum relies on asking young readers to sound out words. At Alturas Elementary School, the district hosted a summer literacy program for students who speak English as a second language. Blaine County School District’s summer school program partnered with tutors from the Lee Pesky Learning Center in Boise to deliver literacy pods for transitioning first graders. (Darren Svan/EdNews)

HAILEY — Experts say reading influences every aspect of your life, so a group of tutors and committed administrators set out each summer to ensure multilingual first graders receive the early literacy instruction needed for their long-term success.

That intervention is increasingly needed as Idaho’s foreign-born population grows. The American Immigration Council reports that one in 12 Idaho workers is an immigrant, who likely leads a household.

School districts like Blaine and Vallivue experiencing an increasing number of multilingual children are discovering new strategies to help them achieve reading performance. Blaine County’s assessment scores show that many students who participated in their reading program last summer advanced from behind grade level to at grade level.

At a round, wooden table in the Alturas Elementary School library, six-year-old Jasmine’s expressive face looked determined as she sounded out the words “and” or “get.”

Every once in a while, she would interject a little Spanish for clarification.

“Sound it out,” her tutor encouraged.

“Ahh-nn-d. Ah-n-d. And,” Jasmine said. ‘G-ehh-t. G-e-t. Get.”

A quick high-five and they were off to the next lesson.

Jasmine was decoding words: to see a string of letters, match those to the letter sound and then blend those sounds together to read a written word. She was one of 40 Blaine County School District first graders enrolled in Lee Pesky’s summer literacy pods for English learners (EL).

EL students are considered at-risk because they speak a language at home other than English, and whose difficulties in speaking, reading, writing or understanding English could deny them the ability to achieve classroom success.

The literacy pods “are transformative in the lives of the children we serve,” said Lindy Crawford, executive director of Boise’s Lee Pesky Learning Center.

Blaine County built the intervention program for EL students through private-public partnerships: federal coronavirus money and private donations to non-profit organizations; it funded summer school staff members, curriculum and the learning pods. Lee Pesky’s participation was funded privately through donations and fundraising, according to the district.

“This program can be a model for other districts,” said assistant superintendent Adam Johnson. “Students in this program exit with a new confidence about their ability to succeed in school.”

Children who don’t get off to a good start in reading find it difficult to ever master the process, according to reading researchers. And the strategies that struggling readers use to get by — memorizing words, using context to guess words, or skipping words they don’t know — are the strategies that many beginning readers are taught in school, which makes it harder for many kids to learn how to read.

Developed by their reading specialists, Lee Pesky’s curriculum is effective because it incorporates the science of reading: research- and evidence-based instructional principles. That scientifically based research informs teachers how proficient reading develops — why some have difficulty, and how to effectively assess and teach those with difficulties through prevention and intervention.

The literacy pods have been successful because of the partnerships they have inspired, said Crawford. “School districts are busy places and collaborating with nonprofits takes additional effort. But the districts who have partnered with us are led by forward-thinking professionals who know that there is power in partnerships.”

Johnson agrees: “This program models the strength of engaging community partners into the education process.”

“Relationships are key to our success”

A Lee Pesky program director, Jahziel Hawley-Maldonado recalled that when one student was asked by her tutor what she learned this summer, she responded, “I learned to love you.”

“Relationships are key to our success,” said Crawford.

According to 2022 State Department of Education data, newly enrolled students who spoke something other than English as their first language made up a significant portion of Idaho’s school-aged population growth.

Idaho’s entire school-aged population ticked up slightly at .03%, from 312,643 to 313,641, or about 998 students. In that same period, the state’s EL population increased by 4.5%, or about 805 students.

The largest percentage increases were in these five districts: Twin Falls enrolled 79 new students, or an increase of 11%; Blaine at 70 students, or 13%; Mountain Home at 36 students, or 16%; Gooding at 37 students, or 26%; and Pocatello at 21 students, or 26.5%.

Because of increases in their EL population over the last few years, Blaine County developed a summer “service component” to their multilingual program.

Originally not a focal point of the summer learning program, “we have moved language learners higher on the priority list of considerations because we have experienced a significant influx of new-to-the-country students in the district,” Johnson said.

The elementary learning program is called Summer Bridge Academic Camp, while the middle school is Find Your Element Academic Camp. There were 300 students in grades 1-5 and 55 students in grades 6-8.

Embedded in the summer camp are the literacy pods: one or two students paired up with an enthusiastic tutor, trained by the Lee Pesky center. About half the tutors are bilingual, though it’s not a requirement. This is where that cohort of 40 first graders received additional instruction, because part of their summer camp was spent in the library learning to read.

“I am convinced that one of the most effective tools that we have to help more students reach proficiency is leveraging additional instructional time,” said Johnson.

The Lee Pesky reading curriculum includes 55 lessons that help develop essential reading concepts: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

- Phonemic awareness develops sound recognition by listening to and repeating the sounds of letters.

- Letter-sound correspondence is developed by displaying a letter and asking learners to say the sound.

- Word building occurs when words are separated into sound parts and students create words using letter tiles that represent the sounds.

- Word cards require students to sound out the word or read the word.

- Spelling skills are developed when instructors say the words and ask students to identify the sounds they hear and write them on paper.

- Automatic word recognition is practiced by reading whole words (“the” — “t” “h” “e” — “the”).

- Sentence reading helps students apply all of these skills along with vocabulary they’ve learned.

- Toward the end of the learning process, they attempt to read a story while the instructor asks comprehension questions.

Lee Pesky tutors work with those incoming first graders over the summer but they also “push into our schools in the fall and throughout the school year,” Johnson said. That added instructional time is beneficial for those students, because Blaine County is experiencing an influx of new multilingual students, gaining 200 more out of a total population of 3,300, he said.

“We meet with them to discuss program goals, and we decide who we partner with based on the fit between their summer programming and the population of students they serve,” Crawford said.

Wood River Valley partnerships launched an innovative early literacy intervention

Maldonado and 10 Lee Pesky tutors were in the field this summer at Alturas elementary and also Vallivue School District’s West Canyon Elementary School, the location of their migrant summer school program. Between the two districts, 62 students completed the program.

The program began in Bellevue, Hailey, Ketchum and Sun Valley in 2020 with approximately eight students as a response to the negative educational effects of COVID.

“It is now part of our operations and allows us the opportunity to reach more students, partner closely with school districts and other nonprofits, and serve young learners who may otherwise never have found their way to our front door,” Crawford said.

The program is a model for others to emulate.

“The Wood River Valley does have a significant number of non-profit organizations, not every district has access to this depth of local programs, but I think every district has their own unique resources that could allow for a similar public-private collaboration,” Johnson said.

“It is fun to see what can be developed when a diverse group, who prioritize the needs of children, collaborate with each bringing their diverse knowledge, skills and resources to the table,” he said.

Crawford added, “We go in with the goal of teaching students to read and we leave knowing that we have touched their lives on a deep and meaningful level.”